Facing the wero: How we put things right

How should you respond biblically when you genuinely support the bicultural journey and value things Māori, yet find yourself having caused offence? That was the position we found ourselves in.

In early 2024, Hope Project (Shining Lights Trust) used an AI‑derived image of a wero during a pōwhiri without rights. It breached dignity and respect and caught the nation’s attention. The greatest harm was not legal. It was cultural and relational. We had replaced the head of a real person — the head being the most tapu part of the body. Far beyond the technical breach, this was a deep offence to a person, to a people, to a place, and to a living tradition. We stopped delivery of the booklet, apologised, fronted up, and entered a tikanga‑based reconciliation process. And we were shown grace we did not deserve.

This article explains what happened, how we responded, and what we learned.

(Weblinks to a public TV news report and also our online apology statement from early in the journey are included as extra references under this article.)

We meant well. That did not matter. We were wrong.

What happened

The intent behind the image was to honour a story about an ancestor of Te Tai Tokerau hapū, Ngāti Torehina, and to give focus and precedence to Māori and the gospel.

We had always ensured rights of use for images. That was our standard protocol. However, when no suitable image of a wero (challenge during a Pōwhiri / welcome onto a Marae) could be found, we used an AI‑edited image, incorrectly believing it was unique and the original from the public domain. It passed our checks, inclusive of over 100 people from all walks of life, without challenge.

Devastatingly, instead of demonstrating honour, the image exposed a gap in our cultural respect. The head — the most tapu part of the body to Māori — was replaced. The sacredness of the person, his people, the place, their tradition, was desecrated. This was a breach of dignity and tikanga.

Our actions were experienced by Māori as another reminder of colonial harm. Māori Christians were hurt also — often told faith in Ihowa opposes Māori identity. We added pain, not help. This also worked against the gospel, rather than for it.

The online reaction was rapid and intense

With the booklet printed and the delivery begun, the original photographer had recognised the photo — the person’s face had been replaced and the background re-organised, yet the individual, place, and event were still recognisable.

We received an email from a relative of the person photographed, suggesting we had an image in our booklet we did not have correct rights for. The email did not specify which photo. We audited all images and called an emergency board meeting — our first in 15 years. Initial requests for more details went unanswered. Two days later, the media story broke.

Word spread online within hours. The first post reached about 50,000 and quickly spread into regional channels — reaching plausibly the hundreds of thousands. Our offence quickly became a rallying point against AI based appropriation from Māori.

The social media experience was not an easy one.

It felt like generations of Māori marginalisation and oppression were being channelled into the threads. Being the target of public anger while choosing to not mount any defence was far from comfortable. My family, the local church we attend, and our ministry were all targeted with some posts that turned personal and discriminatory. This reinforced our decision to prioritise kanohi ki te kanohi (face-to-face) engagement. It wasn’t just about us.

Amid the heat, however, there were measured voices that simply named the offence and challenged patterns of taking — and we agreed with these.

How we sought to put it right

The reconciliation that came about was only possible because of the grace of those we had wronged. With this noted, we could only control our own actions. These were our action steps.

> Letting our actions speak

Once we understood the depth of the offence, we chose not to seek permission to continue with the booklet delivery. Asking would place an unfair burden of grace on those we had wronged. We therefore halted national delivery of the booklet immediately.

This decision carried significant cost. Our relational volunteer network — over 4,000 people across 100 locations — stopped delivery as soon as messages reached them. The volunteers were amazing. The rare occasions where deliveries continued were due to people not yet receiving the instruction, not defiance.

Grace was extended to us in this.

> Choosing openness

With board approval, within the first day of the matter exploding online I entered the primary social media thread personally and identified myself as Director of the Trust. All our media passes across my desk. Responsibility ultimately sat with me.

We focused our efforts on connecting with those most affected — to understand the harm, to apologise, and to find a way forward. Public statements of apology were made via webpages and similar to open conversations. It was not possible or appropriate to engage with every expression of anger online or to my phone or email — as they numbered in the thousands. Priority belonged with those most-directly wronged.

As the issue escalated, public media became involved. We participated openly. There was some surprise among the media that I was willing to be interviewed. One reporter remarked that in 14 years she had never interviewed the actual responsible party in a case like this; often a “token” spokesperson fronts while those at fault hide. We could not do that. We agreed with the substance of the criticism: we had done wrong.

However, these engagements were not easy. I was personally receiving hateful comments and also personal threats through almost every medium of communication possible. I felt battered. It was impossible to know the motives or journey of any person I opened myself up to for a conversation. I had to dig into my faith, trusting that principle that God will honour those who honour him (1 Samuel 2:30). If we do what is right, one step at a time, we will come through. Friends gave encouragement — including friends who are Māori. They engaged without prejudice, never questioning our motives despite our wrongdoing. They looked to our wellbeing first, and then secondly to the issue at hand to see how they could help or encourage a good path. We were blessed!

> Fronting up — the hui

A reconciliation hui was arranged about a month after Easter at a marae near Rotorua belonging to those most affected. We entered with humility: heads low, eyes down, quiet waiata. We were there to stand in repentance.

There were other Christian leaders who came to support us. Our team remains deeply grateful to them all for kindness we will never be able to repay. The tuākana (older siblings) of the New Zealand Church — the Anglican Tikanga Māori church, including Bishop Kito (Tai Tokerau), stood with us. They came to bear our shame, not to defend us, but to share accountability and cover us with their mana. Te Hurihanga Rihari and whānau from Ngāti Torehina (descendants of Ruatara, who’s story was in the booklet) came also. By God’s miracle, he had direct whakapapa (family lineage) to the host marae, even while living in Northland.

The kōrero began in te reo Māori. The offence was named with clarity, grace, and emotion. They explained that this was not just an image that was desecrated — it was a person, representing a sacred tradition, at a sacred event, in a sacred place — Mokoia Island. Whānau connected to the man giving the wero in the original image were also present. The harm extended to them, to their iwi, to their ancestors, and to a tradition handed down over generations.

One kaumatua, pointing to photos on the wall remarked how Christianity had helped their people — even while plausibly most present were not Christian themselves. He pointed to photos of their ancestors who had built the church next door. He remarked that this faith had helped and could yet help their people more. For him, the issue wasn’t with faith in Christ — but with our actions.

When it was our turn to respond, I gave no excuses. I acknowledged my offence as fully and completely as I could. We had breached copyright. We had wronged the person in the image and everyone he belonged to. We had offended Ngāti Torehina, who were connected to the story the image was used for. We had also put Christian Māori in a difficult position — feeling unfairly pulled in two directions.

Grace was then extended.

True grace, by its very nature, is undeserved and our team will forever remain deeply grateful for it. To receive forgiveness from people that we have wronged is humbling.

We greeted one another with hongi. Waiata were sung. We shared kai together. Mana was restored. Reconciliation was completed.

What we learned

- Good intentions are not a safeguard.

- Values and tikanga must shape the process, not only the purpose.

- Relationship precedes representation.

- Indigenous stories and imagery needs relational consent; design must be in relationship with the people of the story.

- Treat indigenous content with caution.

- Build extra checks with cultural advisors. AI increases cultural risk, not reduces it.

- Colonial harm is not abstract.

- Modern day missteps can reopen real, painful historic wounds. Respond with humility and care.

- A responsibility to do all we can to reconcile with others always sits with us (Matthew 5:23-4)

- Humility creates a pathway for mana to be restored

- “Whoever heeds correction is honoured.” (Proverbs 13:18.) “Humility comes before honour.” (Proverbs 15:33.)

- Honour comes from listening not defending, owning the truth – not hiding from it, while working to not repeat the error.

Choosing to walk with integrity rather than to defend ourselves was the only possible choice, because we had done wrong. This did lead to restoration.

- A man who is Māori stopped me when out shopping, having recognised me. I engaged politely while ready for another criticism. He thanked me for engaging with humility. He held to the Christian faith. He knew many of those involved. He said, “You are the real deal”, and “Well done.”

- Another lady pulled me aside to talk as I entered a church. While Pākehā she held strongly to the bicultural value and had stopped coming to church because she couldn’t see how Christianity and our nation’s history could be reconciled. Seeing our actions on the TV convinced her that this was possible. As a result she decided to start going to church again.

We will never know the damage that could have resulted had we not engaged as we did — despite the enormous cost this was personally and to the work at that time. People are more important than things; and even a gospel booklet is still just paper.

What we should have done

If we needed an image of a wero, the right approach would have been relational. We should have approached the hapū connected to the story of Ruatara and his invitation to Marsden and the gospel — in this case Ngāti Torehina — to ask whether a suitable image could be provided or created. That would honour both the story and the people within it.

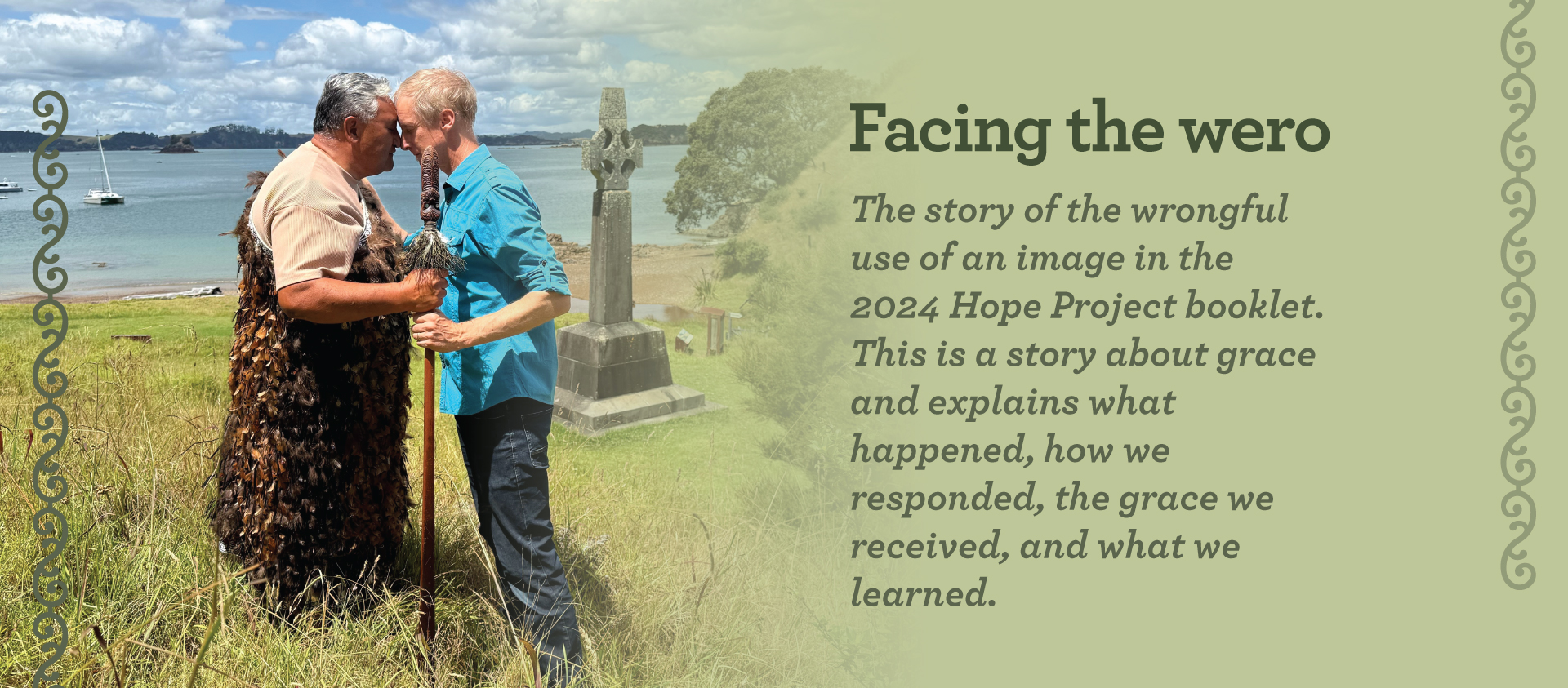

The image found with this article illustrates the difference. When asked about a suitable image for this article, two Ngāti Torehina kaumatua suggested this photo be taken. It includes myself with Te Hurihanga — representing Ngāti Torehina. It is taken at Rangihoua Bay, where Ruatara first invited Marsden to share the Christian message of love and peace. It represents an extension of grace from Ngāti Torehina toward us for our wrong-doing, while putting right the process that should have been taken. It is symbolic of this story — as also of the message their ancestor Ruatara enabled to be told in these lands.

Design that seeks to honour a story is good. Design that is in relationship with the people of the story is better.

Other references

- TV News Article: From ‘Te Ao with Marama’ — view here . At 11 minutes length, it reflects well the depth of hurt we caused, while also the process that led to eventual reconciliation and grace.

- Written Apology: Dated 18th April 2024, an apology statement purposed to update wider audiences on the process of the apology and reconciliation process. View here.